China’s Investments in Malaysia: Too Much, Too Fast, Too Soon

Selangor and Penang – both opposition-held states – attract among the highest levels of foreign investment in Malaysia.[1] We are supportive of the current open trade regime that has been Malaysia’s proud tradition since the early trading days at the Straits of Malacca. We highly regard past posturing at the regional level which are peaceful, neutral and free – ZOPFAN. Whichever superpower it may be is welcomed, so long as it adheres to the prudent framework of symbiotic cooperation.

However, we differ starkly from the Barisan Nasional government under Prime Minister Najib Razak’s leadership on our emphasis on caution and moderation. We also disapprove of the current government’s practice of escalating financial liabilities which leads to aggravated risks and disadvantaged decision-making.

As such, we view with caution China’s bountiful investments into Malaysia. As a simple measure of magnitude, the 14 MOUs that Prime Minister Najib Razak signed with China last November stand grandly at RM143.6b,[2] equivalent to 55 percent of our 2017 federal budget. Najib returns to China again for more this May, barely half a year after these deals were inked.

Indeed, foreign investment remains important for economic growth. But as with any venture, we must adopt moderate and prudent approaches to cope with potential risks. Deals concluded too soon increases the plausibility for exploitation, collusion and corruption. Be frantic for China’s good graces and greedy for its wealth, and we stand to lose leverage over Malaysia’s own needs and priorities.

Alignment with superpower interests at the expense of domestic concerns

Only recently did centre-left think tank Institut Rakyat hold a closed-door roundtable on the impact of China’s investments into Malaysia. Esteemed economist Prof. Jomo Kwame Sundaram noted that Malaysia has been consistently open to foreign direct investment (FDI) since its founding days. However, what has fundamentally changed, he said, is our prudence and watchfulness over foreign ownership of land and assets.

For example, Forest City is developed through a 66:34 joint venture between China’s third largest property development company Country Garden and Johor’s little-known Esplanade Danga 88 Sdn Bhd. As of February 2017, Chinese nationals own 70 percent of the homes that have been sold in Forest City.[3] Other Chinese investments, including Melaka Gateway and the East Coast Rail Line, are also predominantly real estate developments.

China’s FDI buries our fiscal mismanagement, but it stops short from boosting the economy

China’s helping hand comes when Malaysia faces the ramifications of severe fiscal mismanagement. For instance, scandal-ridden 1MDB was relieved of its debt obligations when state-owned enterprise China General Nuclear Power Corp purchased all of the former’s energy assets, bestowing it RM9.83b in cash.

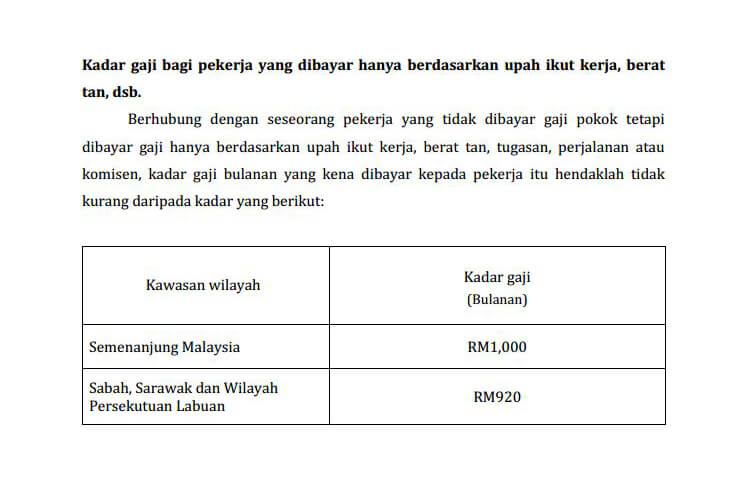

Contrary to accepted conventions, FDI provides cutting-edge technology that strengthens a country’s economy — this is not the support that China is giving. Malaysia has been noted profoundly as a victim of premature deindustrialisation, for shifting its focus onto services without having gone through thorough industrialisation. Yet, decades onwards, we continue to rely excessively on cheap foreign labour, forgetting to invest in technology while nurturing a skilled, local workforce. In the long term, this depresses wages while our cost of living continue to rise.

Thus, China’s sizable investments come not when the government is showing the political will to upgrade our workforce – in fact, our budget for higher education has been slashed one year after another. FDI to enshroud fiscal mismanagement must not be misconstrued for economic progress.

Foreign investment is never unconditional

But, it is not just Malaysia that China has drawn into its embr

ace. China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative seeks to connect China to Asia, the Middle East, Europe, and Africa by way of gargantuan infrastructure investments.[4]

But foreign investment is never unconditional. A deep dive on the Sino-Cambodia relationship by the International Policy Centre of the University of Michigan show that although both countries first reaped significant rewards, China’s mammoth investments are now manifesting as domestic political problems in Cambodia.[5]

What began as preferential treatment led the Cambodian government to grant a disproportionate number of land concessions to Chinese developers. Consequently, since 2003, more than 400,000 Cambodians have become victims of land grabs or evictions.

All this is to say that considering the realm of politicalpower play, wherein China’s ascendancy is a force to be reckoned with, the enthusiasm that follows with its investments must be coupled equally with caution.

Beyond its grip on the economy, China has also expanded its influence militarily. It is no secret that China has been building artificial islands, possibly constructing airstrips and surveillance structures.[6] With its military advantage amplified, China is more able to negotiate matters on its own terms. Thus, mind the snug Malaysia-China relationship, because the elephant in the room is none other than the territorial dispute at the South China Sea. Malaysia should temper risks associated with regional political conflicts, but an undeterred influx of investments only escalates risks. If prevalent in the region, the power balance will tilt away from solidarity with ASEAN to being in China’s good books.

Developing a Regional Response

The diffusion of ASEAN solidarity is worrying, as no ASEAN country in and of itself can stand up to China. In 2015, the economic powerhouse represented 17.85 percent of the world economy.[7] In contrast, ASEAN’s largest economic player, Indonesia clinched only 1.39 percent.[8]

At this year’s World Economic Forum-ASEAN, I was privileged to speak alongside several distinguished panelists, probing a pertinent regional issue that is the ASEAN way. One issue that surfaced prominently and repeatedly is the lack of political will of individual countries — which extends to ASEAN as a collective — to make tough decisions.

Each country’s preoccupation with its national sovereignty imperils the community’s priorities. In Professor Danny Quah’s words, “This (mentality) cultivates an atmosphere that is akin to the politics of envy across the ASEAN community.”[9] With this in mind, we must not subject ourselves to a rat race, one which ends only with increasing servility to China across ten countries.

Clearly, what would put Malaysia or any other ASEAN country in a position of strength is for ASEAN to face China in unity.

For 50 years, we held our national sovereignty tightly within our clutches, afraid of relinquishing power to ASEAN as an association. But should we fall down the slippery slope of taking China’s investments for granted, we would inadvertently yield to a greater, more controlling power.

After all, repercussions of an unequal exchange of benefits will only strike later. Thus, I urge our leaders to be prudent, and to not yield to instant gratification that comes with soft loans, cash deals and gargantuan investments.

It’s time for Malaysia to regain control of its economic and political and leadership.